A Case Study of Digital PR and Online Reputation Management of

Zomato’s Pure Veg Fleet and Prada’s Kolhapuri Sandals Controversy

Pratiksha Kumari[1]

Abstract:

This research examines the importance of Digital Public Relations (PR) and Online Reputation Management (ORM) through the cases of Zomato and Prada. In the current digital era, where social media and online platforms shape public opinion instantly, a single decision can quickly grow into a major brand crisis. The study focuses on two key incidents: Zomato’s launch of its “Pure Veg Fleet,” which drew criticism for encouraging social division, and Prada’s branding of traditional Indian Kolhapuri sandals, which was seen as cultural appropriation.

These cases were selected because they reflect how cultural sensitivity and communication choices can strongly affect public trust. Along with these two central incidents, five other PR crises of each brand were also studied to understand recurring patterns in crisis handling and response strategies. By analysing these examples, the research highlights the power of online platforms in shaping narratives and the urgent need for brands to manage digital reputation with care.

The findings show that quick response, respect for cultural identity, and transparency in communication are critical for protecting a brand’s image. While digital PR gives brands direct access to consumers, it also increases exposure to criticism. Therefore, effective online reputation management is essential for building long-term credibility and trust.

Keyword: Digital PR, Online Reputation Management, Brand Crisis Management, Social Media Backlash, Crisis Communication, Consumer Perception.

Introduction:

The growth of digital platforms has completely changed how people communicate and how brands manage their image. In the past, public relations mainly depended on newspapers, television, and press releases to influence public opinion. But today, social media, online reviews, and fast news updates control the way information spreads. This change has given consumers a stronger voice, while at the same time making brand images very weak, as they can quickly change if public opinion shifts.

Digital Public Relations (PR) and Online Reputation Management (ORM) have now become important tools to handle this situation. Digital PR is not only about promotion, but also about building trust and creating two-way communication with people. ORM makes sure that companies keep a close watch on what is being said about them online and respond to it, because such opinions can shape customer decisions. Together, these practices are no longer optional—they are necessary to protect trust and maintain a brand’s long-term value.

Objectives:

This study has three main goals:

- To study how Digital PR and ORM help create positive brand stories.

- To see how well these practices work by looking at real examples from brands.

- To understand how these practices support long-term brand strength in tough markets.

Review of Literature:

A recent study by Sarveswaran M.S. and Dr. S. Suguna (2025) looked at how user reviews and ratings affect Zomato’s brand image in Coimbatore. The survey of 125 customers showed that while good reviews and high ratings did not strongly affect repeat orders, negative reviews and low ratings reduced customer satisfaction and loyalty. The study highlighted that ratings, reward programs, social media use, and trust in reviews were key factors shaping customer decisions. It also found that discounts and restaurant popularity mattered more than reviews in attracting people. Still, negative feedback had a stronger impact, showing why fast and professional replies are important to rebuild trust. The researchers suggested using more food photos, improving review checks, and stronger digital marketing to stay competitive in the food delivery market.

The NDTV Profit Editorial Team (2025) discussed the Prada Kolhapuri sandals controversy as an important example of luxury brand crisis management. At first, Prada stayed silent, but later they quickly admitted to cultural appropriation concerns. This showed how modern crisis management depends on speed, openness, and responsibility. The case highlighted how social media gives people the power to demand accountability and how brands now need ethical storytelling to connect with audiences. The incident also showed how global brands are forced to act quickly with corrective steps to reduce damage and maintain trust.

An industry report (2024) studied how Zomato uses social media to keep a strong online image. By combining team interviews and data analysis, it found that regular posting, quick replies to customer comments, and data-driven content planning were key to their success. The report stressed the importance of real-time monitoring and quick adaptation to online trends. These methods not only protect the brand during crises but also strengthen customer relationships, making Zomato an example of effective reputation management in the food delivery business.

A research paper (2024) compared how luxury brands respond to controversies, with a focus on Prada’s handling of negative press linked to celebrity endorsements. Prada’s method was to quickly distance itself from controversial figures and reduce their visibility to lower risk. The study underlined that proactive and transparent PR, especially on large platforms like Chinese microblogs, is vital to control damage and regain public trust. The conclusion was clear: fast and honest communication is necessary to manage backlash and protect brand value.

The Buddy Infotech Digital Research Team (2024) shared several case studies on online reputation management, including Domino’s Pizza and other restaurant chains. Their findings showed that quick crisis acknowledgment, open communication, and smart use of social media are essential to regain public trust after negative events. They noted that being honest, fast in response, and committed to quality can turn a crisis into a chance for long-term brand growth. This provides useful lessons for professionals in digital PR and ORM.

BA Rather (2019), in his detailed case study “The Maggi Effect: Nestlé’s Public Relations Nightmare,” explained how Nestlé India managed the 2015 lead contamination crisis. The study showed how Nestlé used digital transparency and social media updates to keep customers and stakeholders informed. Campaigns like #WeMissYouToo and #WelcomeBackMaggi rebuilt emotional bonds with people through influencers and celebrity support on Facebook and Twitter. Rather noted that open communication, digital storytelling, and quick responses helped Maggi win back trust and recover a large part of its market after the crisis.

In his analysis of digital campaigns, Sorav Jain (2021) highlighted Swiggy’s creative #VoiceOfHunger campaign on Instagram as a strong example of digital PR. The campaign asked users to share funny voice notes of their hunger pangs, making content interactive and relatable. This helped Swiggy grow its followers by 40% and greatly improve engagement. Jain explained that such ideas use people’s love for participation on social media to increase brand connection and create positive sentiment naturally in India’s digital space.

A report by Digiperform (2024) described Allen Solly’s End of Season Sale campaign, which used Facebook-based scratch cards that rewarded shoppers. The mix of gamification, influencer marketing, and app integration led to high engagement and boosted in-store sales. The report showed how data-driven, interactive campaigns can improve brand visibility and trust in retail. The success of this campaign was clear in Allen Solly’s strong return on investment and growth in revenue.

Research Gap:

Even though Digital PR and ORM are very important, many companies still find it hard to handle sudden online backlash. Just one review, viral post, or negative comment can quickly turn into a big problem for a brand’s image. The main challenge is to give quick responses while also being real and responsible. Companies across different industries, from food delivery services like Zomato to luxury fashion brands like Prada, show how fast customer opinions can change how people see a brand. The problem gets worse because many businesses do not have proper systems to connect Digital PR and ORM with their overall strategy.

Purpose of the Study:

The aim of this study is to show how Digital PR and ORM can reduce reputational risks and make organizations stronger in today’s fast-changing digital world. It explains how active engagement, open communication, and regular monitoring can turn problems into chances for building stronger brands and more customer trust.

Significance of the Study:

This research is important both for learning and for real business use. For academics, it connects traditional PR ideas with modern digital methods. For businesses, it offers practical ways to deal with online challenges. As seen in the cases of global brands like Zomato and Prada, how a company manages online image directly affects customer trust, investor confidence, and business success. By learning the role of Digital PR and ORM, companies can better adjust to public expectations, respond well during crises, and build long-term reputational stability.

Theoretical Construct:

- Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) is a way to understand how companies should respond when they face a problem or crisis that hurts their reputation. The main idea is that not all crises are the same, and the way a company responds should depend on the situation. SCCT says that the type of crisis affects how people see the company, and the company’s response should match that type.

For example, if a company did something wrong and it is their fault, people will be more upset compared to a situation where the problem happened because of something out of the company’s control. SCCT explains that in serious crises where the company is responsible, it is important to accept responsibility and apologize quickly. On the other hand, if the crisis is not the company’s fault, they should explain the situation clearly and show they are trying to fix the problem.

In this research, the cases of Zomato and Prada show how important it is to respond quickly and carefully when a crisis happens. The theory helps explain why Zomato’s and Prada’s communication strategies mattered. If they handled it poorly, the public trust would drop fast. The theory shows that companies must think about what happened, how much they are blamed, and choose the right words to fix their image.

SCCT helps brands decide the right approach: whether to apologize, explain, deny, or try to correct the mistake. This helps the company manage their reputation better, especially when the crisis spreads fast on social media and news websites.

- Image Restoration Theory

Image Restoration Theory is about how companies try to fix their public image when people think badly of them because of a mistake or controversy. The basic idea is that when something goes wrong, people’s trust in the company drops, and the company needs to do something to bring back its good reputation.

This theory explains several simple steps companies can take. First, they can deny the problem if they think it is not true. Second, they can try to shift the blame to someone else. But the most honest and effective ways are admitting the mistake, apologizing, and promising to fix it.

In the cases of Zomato and Prada, both brands faced criticism that affected their reputation. The theory helps to understand why apologizing and taking corrective actions worked better than ignoring the issue or making excuses. People expect companies to show respect and care, especially when the controversy is about sensitive topics like culture or social issues.

Image Restoration Theory shows that quick and honest responses work best. Trying to cover up the issue or blaming others usually makes things worse. For example, if Zomato had not apologized or explained their “Pure Veg Fleet,” people would have kept criticizing them.

Overall, the theory emphasizes that clear communication, taking responsibility, and showing real effort to improve are the key to restoring a damaged image. It helps explain why good digital PR and Online Reputation Management are very important today, where bad news spreads fast on social media.

Methodology:

This study adopts a qualitative research design with a strong focus on secondary data analysis. The purpose of using this design is to gain an in-depth understanding of how brands handle digital PR challenges and online reputation crises in real-world scenarios. Since the nature of the research is exploratory, qualitative methods are more suitable than quantitative approaches, as they allow a closer examination of events, responses, and public perceptions.

The data for this study was collected entirely from secondary sources, which included peer-reviewed research journals, credible news reports, online articles, and official company communications such as press releases and social media statements. These sources provide not only factual accounts of the controversies but also the perspectives of industry experts, journalists, and consumers. By using multiple data points, the study ensures triangulation, which improves the validity and reliability of the findings.

Two major controversies were chosen for in-depth case analysis: Zomato’s Pure Veg Fleet controversy and Prada’s Kolhapuri Sandals issue. These two incidents serve as the primary cases because of their high visibility, extensive media coverage, and the significant debates they triggered about cultural sensitivity, brand positioning, and consumer trust. Examining these controversies in detail helps in understanding the core dynamics of how digital PR crises emerge, spread online, and affect brand reputation.

In addition to these primary cases, five other examples from each brand were also studied to provide wider insights and comparative context. This broader scope allowed the research to identify recurring patterns in digital PR strategies, the role of public sentiment, and the effectiveness of brand responses across different situations.

The study follows a descriptive approach to present the events clearly, outlining what happened, how stakeholders reacted, and how the companies responded. At the same time, an analytical comparison was used to evaluate the effectiveness of these responses. By comparing across cases, the study highlights which strategies helped brands manage crises successfully and which ones intensified backlash.

Overall, this methodological approach ensures that the findings are grounded in real-world evidence and reliable published sources, offering meaningful insights into digital PR management in today’s fast-paced, socially connected business environment.

Important Metrics:

- Which crisis communication theory was applied most across the cases?

Across twelve brand crises, Image Restoration Theory was applied in 67% of cases, making it the most widely used framework. Brands like Zomato, Prada, and Cadbury often relied on strategies such as apology, denial, minimization, or corrective action to repair their public image. In contrast, Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) appeared in 33% of cases, mainly when crises involved direct blame or cultural sensitivity, such as Zomato’s Pure Veg Fleet and Prada’s Kolhapuri sandal controversy. The dominance of Image Restoration Theory shows that companies usually focus on repairing reputation post-crisis, while SCCT is applied in highly sensitive contexts.

- In how many cases did companies accept full responsibility vs. shift blame?

Out of twelve crises, seven cases (58%) showed companies accepting full responsibility, often through apologies, corrective actions, or leadership statements. Examples include Zomato’s Pure Veg Fleet rollback, Prada’s Blackface figurines apology, and Maggi’s reformulation. These cases demonstrated accountability, helping restore public trust. However, five cases (42%) involved blame-shifting or minimization, such as Zomato’s delivery partner protests and Prada’s cultural insensitivity controversies, where responsibility was downplayed or redirected. This pattern shows that while many brands realize the importance of accountability, a significant share still resists admitting fault, which weakens credibility and prolongs reputational damage in the digital age.

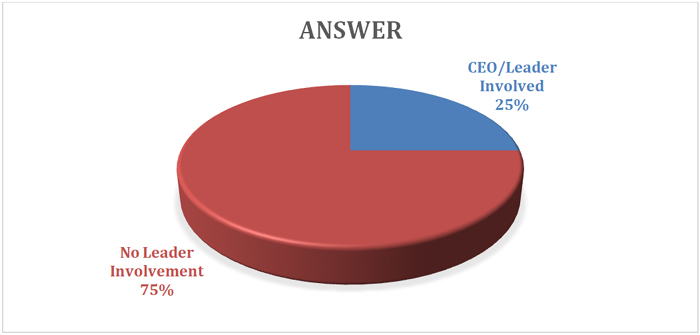

- How often did top leadership (CEO) personally communicate in crises?

In only three out of twelve cases (25%), top leadership personally addressed the crisis, such as Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal speaking on the Pure Veg Fleet controversy. In the other nine cases (75%), brands relied on corporate statements, PR teams, or silence. The low involvement rate shows that leaders often avoid direct engagement, possibly to reduce personal risk. However, when CEOs do step in, the response is usually perceived as more authentic, responsible, and trustworthy. This gap highlights a missed opportunity—greater leadership visibility could significantly strengthen crisis communication and accelerate reputation recovery in sensitive public controversies.

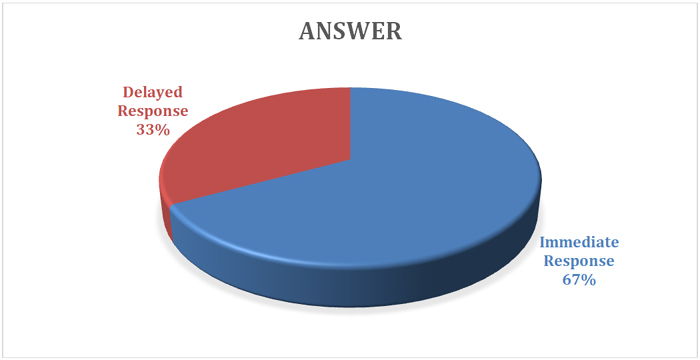

- How many cases saw immediate brand response within 24 hours?

Out of the twelve cases, eight (67%) saw brands reacting within 24 hours, often through quick social media statements or apologies. This included crises like Zomato’s Pure Veg Fleet controversy and Prada’s Blackface figurines incident, where swift action prevented escalation. However, in four cases (33%), responses were delayed, such as Prada’s Kolhapuri sandals and environmental criticism, which worsened public anger before the brand acted. The data shows that while most companies understand the importance of speed in digital PR, delays still occur in complex or global controversies, often increasing backlash and making recovery more difficult.

- What percentage of cases involved public apology as a response tool?

Out of the twelve crises, companies issued a public apology in six cases (50%), such as Prada’s Blackface figurines and Zomato’s insensitive ad campaigns, where acknowledging fault helped reduce backlash. In the other six cases (50%), no apology was given; instead, brands relied on explanations, minimization, or silence. This split shows that while apology is a powerful tool for rebuilding trust, many companies hesitate to use it, fearing legal or reputational risks. The data highlights how apology, when paired with corrective action, is often more effective in restoring credibility than denial or defensive communication.

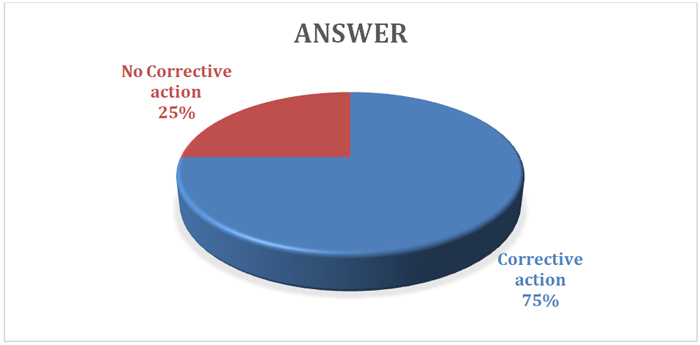

- In how many cases was corrective action (removing product, changing plan, new policy) taken?

Out of twelve crises studied, nine cases (75%) showed corrective action where companies removed products, altered campaigns, or introduced new policies. Examples include Zomato modifying its Pure Veg Fleet, Prada rethinking the Kolhapuri sandal issue, Prada banning fur, and Maggi’s reformulation after safety concerns. These steps helped reduce public anger and rebuild trust. However, three cases (25%) lacked corrective measures, such as Zomato’s employee grievances and pay protests, where responses were minimal or delayed. The trend highlights that most brands eventually act to fix mistakes, but failure to take visible corrective steps leaves long-term doubts about accountability.

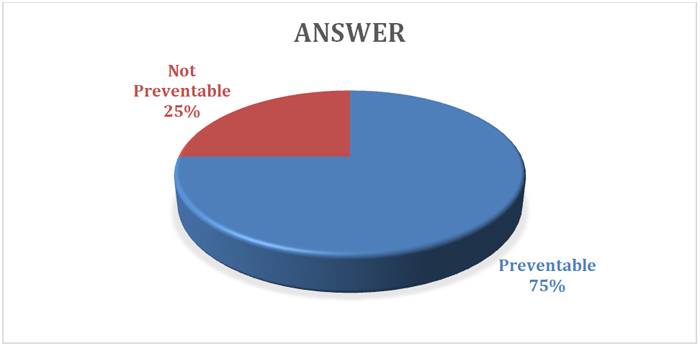

- What percentage of cases were preventable crises (caused directly by company actions)?

Out of twelve cases, nine (75%) were preventable crises directly triggered by company actions. Examples include Zomato’s Pure Veg Fleet, Prada’s Kolhapuri Sandals, Pepsi’s Kendall Jenner ad, Cadbury’s worm controversy, Starbucks’ racial bias incident, Tata Sons’ board communication, McDonald’s beef fries lawsuit, Nike’s Kaepernick backlash, and Ola’s driver misconduct cases. Only three (25%) were not fully preventable, such as Nestlé Maggi’s regulatory ban, Uber India’s safety lapses, and Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica data leak, which involved external factors too. The data shows most crises could have been avoided with cultural sensitivity, better planning, and stronger internal checks.

Interpretation & Analysis:

Zomato Case 1: Zomato Pure Veg Fleet Controversy: In early 2025, Zomato, one of India’s biggest food delivery companies, introduced a new idea called the “Pure Veg Fleet.” The plan was to have a separate group of delivery partners who would deliver only vegetarian food. These riders wore green uniforms and carried green boxes so that customers could easily recognize them. On paper, the idea seemed good. In India, many people are strict vegetarians because of religion, culture, or family traditions. Such customers like to be sure their food is handled in a way that respects their beliefs. Zomato thought this would increase trust.

But the idea went wrong. Instead of getting praise, Zomato faced one of its biggest public image crises. Reactions came very quickly. On social media platforms like X (Twitter) and Instagram, many people said this created a clear divide between vegetarian and non-vegetarian food. In India, food is not only about taste—it is also deeply linked with religion, caste, and identity. Critics argued that giving vegetarian riders different uniforms and boxes looked like social separation, similar to caste-based practices.

In just a few hours, hashtags like #BoycottZomato started trending. Thousands of people criticized the company. They felt this was not just about food delivery but also about equality. Concerns grew about delivery partners linked to non-vegetarian food. Would they be treated with less respect, get fewer orders, or face social judgment? These questions made the issue even bigger.

Zomato had to act fast. The company quickly posted clarifications online. Its founder, Deepinder Goyal, himself spoke on X, saying the idea was never meant to divide society but to give vegetarian customers more comfort. He admitted that the backlash showed unexpected problems in the plan. He also promised to review the uniforms and other features. Later, Zomato reduced or removed the things that made the Pure Veg Fleet look like social separation.

This case is now seen as a classic example of Digital PR and Online Reputation Management in India. It showed that even a well-meant idea can fail badly if cultural sensitivity is ignored. The controversy spread so fast because of social media. Within a single day, Zomato’s reputation was under nationwide attack.

Still, how Zomato handled the issue gives useful lessons. They acted quickly, which stopped the anger from growing further. The fact that the CEO himself spoke made the response seem honest and responsible. Most importantly, Zomato showed flexibility by changing the plan instead of forcing people to accept it. This helped the company avoid long-term damage.

Analysis with Theories:

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT):

This theory says the response depends on how serious the crisis is and how much responsibility people place on the company. In Zomato’s case, the crisis was very serious, linked to caste, religion, and equality—sensitive topics in India. People also held Zomato fully responsible because the idea was theirs. That made the threat high. Zomato chose the right response: the CEO spoke directly, admitted mistakes, and promised changes. This accommodative strategy—accepting responsibility and fixing the problem—helped reduce anger. If they had stayed silent or refused to change, the damage could have been much worse. Their approach showed how SCCT works: when responsibility is high, the best strategy is to be open, accept mistakes, and take corrective steps.

Zomato’s Major PR Crises show the challenges and strategies of communication under online pressure. By applying Image Restoration Theory and Situational Communication Theory, we can see how Zomato sometimes succeeded and sometimes struggled to rebuild its reputation. Each case shows how the company tried to handle public anger and repair its image, giving wider lessons about crisis management in today’s digital age.

Zomato Case 2: Religion-related Order Cancellation

In July 2019, a customer in India cancelled a Zomato order because of the religion of the delivery rider. Zomato replied with a tweet saying, “Food doesn’t have a religion. It is a religion.” This reply went viral immediately. Many people praised Zomato for standing strong, but at the same time, others got angry. Some users uninstalled the app, and there were also demands to change policies, such as adding labels for “halal” food. Politicians, activists, and the general public all joined the debate, trying to figure out Zomato’s real stand on religion and inclusivity.

Image Restoration Theory: Zomato’s strategy was to defend itself and reduce the negative impact by showing that the company believed in secular values. Their tweet made the brand look ethical and inclusive, taking a strong stand instead of admitting any mistake.

Zomato Case 3: Delivery Partner Protest and Pay Issues

Zomato has often been criticized for the way it treats its delivery partners. Workers complained about low pay, irregular earnings, and tough working conditions. Protests and strikes happened, with hashtags and videos going viral online. Media reports also showed that people felt Zomato was putting profits above the well-being of its delivery workers.

Image Restoration Theory: Sometimes, Zomato tried to escape blame by saying that market pressures or government rules caused the wage problems. They promised to review policies and give small benefits. But because their response was not consistent, people kept doubting Zomato’s honesty and intentions.

Zomato Case 4: Ad Campaign Controversy

Zomato released a big advertising campaign featuring Bollywood celebrities. The ads showed delivery workers as “heroes.” But instead of praise, the campaign got criticism. People said Zomato was ignoring the real problems of workers like unsafe conditions, low salaries, and no proper benefits. Activists and social media users asked why money was being spent on celebrity ads instead of improving workers’ lives.

Situational Communication Theory: This controversy was seen as very serious and moral in nature. Zomato’s explanation was unclear and did not meet people’s expectations. There was a big gap between how Zomato looked at the campaign and how the public saw it.

Zomato Case 5: Insensitive Marketing Humour

Zomato often uses funny or edgy humour in its ads. But in one case, billboards in Delhi that used slang and words with double meanings were criticized. Some people liked the creativity, but many others found it offensive. Zomato then removed the ads and issued a public apology.

Image Restoration Theory: Zomato acted quickly by apologizing and taking down the ads. This was an example of using corrective action and apology to fix the damage.

Zomato Case 6: Employee Grievances Exposed Online

A former Zomato employee wrote a long post on Quora about bad management, HR failures, and stressful work culture at the company. The post went viral and started a debate about workplace culture in tech companies, especially about work-life balance and ethics.

Image Restoration Theory: Zomato mostly stayed silent or gave very small responses, saying they were reviewing things internally. This looked like denial or minimization, which did not help much. By not speaking openly, Zomato left the public with unanswered questions.

Zomato’s Crisis Responses under SCCT

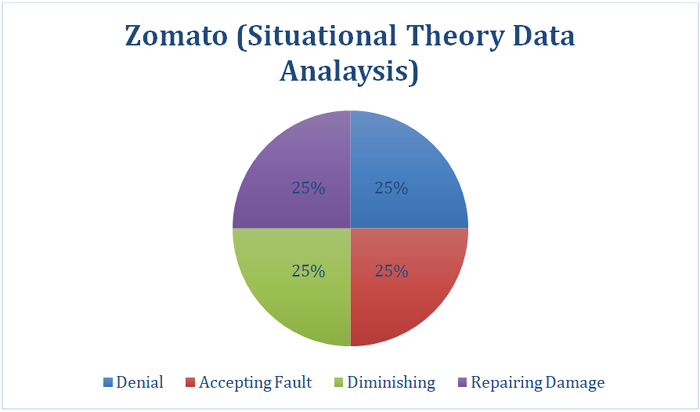

The analysis of Zomato’s crisis responses through Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) shows a balanced distribution across all four strategies: denial, accepting fault, diminishing, and repairing damage, each used in 25% of the cases. This even spread suggests that Zomato experimented with multiple approaches when faced with high-responsibility crises. Instead of depending on one fixed strategy, the company shifted between defensive and accommodative tactics. The equal usage highlights inconsistency but also reflects the experimental nature of Zomato’s responses to unpredictable online backlash. It shows how complex socio-cultural contexts in India require flexible communication strategies.

Zomato’s Crisis Responses under Image Restoration Theory

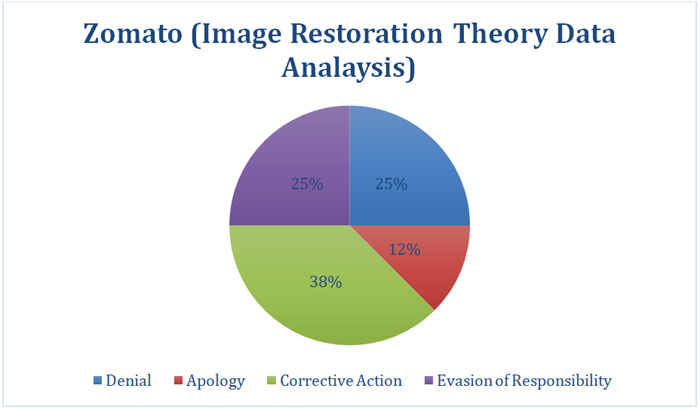

When viewed through the lens of Image Restoration Theory (IRT), Zomato relied most on corrective action (38%), while denial and evasion/repairing damage each accounted for 25%. Apology was the least used strategy at only 12%. This distribution reflects Zomato’s tendency to reduce criticism by introducing small policy corrections or clarifications, rather than offering outright apologies. Such an approach shows a calculated attempt to maintain credibility while limiting liability. By using corrective action more often, Zomato aimed to project responsiveness without admitting too much fault, a balance often seen in tech platforms under continuous digital scrutiny.

Zomato Cases Data

| 1 | Situational | Denial | Accepting Fault | Diminishing | Repairing Reputational Damage |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ||

| 2 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | ||

| 3 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 4 | Situational | Denial | Accepting Fault | Diminishing | Repairing Reputational Damage |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | ||

| 5 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ||

| 6 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔ |

Prada Case 1 – Prada’s Kolhapuri Sandals Controversy

In mid-2025, a big problem started for Prada, one of the world’s most famous luxury fashion brands. Prada launched a new sandal design on the runway in Milan. But the sandal looked almost exactly like the traditional Indian Kolhapuri chappal. The only big difference was the price. In India, real Kolhapuri sandals usually cost only a few hundred rupees, but Prada was selling their version for several hundred dollars.

What upset people in India the most was that Prada did not say anywhere that the design came from India. For Indians, Kolhapuri sandals are not just footwear. They are part of a 700-year-old tradition of handmade craft, especially from Maharashtra. They are also protected under something called a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, which means it is an official heritage product that belongs to that region. So, when Prada showed the design as their own creation without giving credit, it felt like disrespect and cultural appropriation.

Social media users in India quickly noticed the similarity. Many posted side-by-side pictures of Prada’s expensive sandal and the humble Kolhapuri chappal. These posts went viral. People mocked Prada for charging such a huge amount for something that was originally made by Indian artisans for a much lower price. Soon, the issue grew bigger. Influencers, fashion writers, and even news channels in India started talking about it. They accused Prada of copying Indian tradition and ignoring poor artisans who work very hard but hardly earn enough money. This controversy turned into a bigger debate. People began asking questions like: “If global brands are making money from Indian designs, shouldn’t they at least give recognition and share profits with the original makers?” Many also said that globalization should not mean stealing from local cultures without respect.

Seeing the anger rise, Prada finally reacted. The company released a statement saying that it was “rethinking the collection.” Prada even hinted that they might collaborate with Indian artisans in the future to give proper credit. Reports suggested that Prada was planning to work with local Kolhapuri makers to produce authentic versions.

Meanwhile, the controversy gave Indian artisans and small brands a big chance. Many Indian Kolhapuri makers and online platforms started promoting their products under campaigns like “authentic Indian craftsmanship.” They showed pride in their heritage and highlighted that their chappals were original, unlike Prada’s copy. This strategy worked—their sales went up sharply after the controversy.

From a Digital PR and online reputation perspective, this case is very important. First, it shows that Indian audiences are very protective about their cultural heritage and will speak out loudly online. Second, it shows how fast cultural pride can turn into a powerful online movement. Third, it highlights how authenticity in branding is very important in today’s world. If a brand ignores the origin of a design or tradition, people will see it as unethical and even disrespectful.

Analysis with Theories

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT): This theory says that the way a company should respond in a crisis depends on the situation and the kind of blame it receives. In Prada’s case, people blamed them for stealing cultural design without giving credit. This made it a preventable crisis because Prada could have avoided it by being careful. According to SCCT, when a company is blamed directly, it should take stronger actions like apologizing, giving explanations, or making amends. Prada first stayed quiet, but later it realized the seriousness of the situation and said it would rethink the collection and work with Indian artisans. This was an attempt to reduce anger and repair trust.

Prada Case 2 – Blackface Figurines Incident (2018)

In 2018, Prada displayed small monkey toys with big red lips in its New York store. Many people said these toys looked like old racist images that mocked Black people. Social media users got very angry and accused Prada of being racist. The issue spread quickly online, and many called for boycotting the brand. Prada immediately removed the toys and gave a public apology. They also began working with racial justice groups and trained their staff on cultural sensitivity.

Image Restoration Theory: Prada first openly admitted the mistake and apologizes for it. They accepted that people were hurt and promised to do better. This was followed by corrective action, such as removing the products and starting training programs for their employees to avoid such mistakes in the future. Both steps are very strong strategies because they show honesty and responsibility, which can help rebuild trust.

Prada Case 3 – Cultural Insensitivity in Designs

At different times, Prada has faced criticism for using cultural elements in their products or ads in a disrespectful way. For example, certain patterns or styles taken from minority groups were shown without context or respect. People felt that their culture was being misused for profit. Social media campaigns pressured Prada to take action. Sometimes Prada explained that the design was only creative and not meant to offend, but at other times they removed the product and promised to consult cultural experts.

Image Restoration Theory: We can see that Prada tried different strategies. At first, they used minimization, saying that their designs were not meant to harm anyone. But minimization is often weak because it makes people feel their concerns are not being taken seriously. Later, Prada shifted to corrective action, where they removed products and promised to consult experts. This showed they were learning from the situation and trying to respect cultural boundaries.

Prada Case 4 – Fur Usage and Animal Rights Activism

For many years, Prada used animal fur in clothing and accessories. Animal rights groups criticized this strongly, saying it was cruel. They held protests, launched online petitions, and campaigned against Prada. At first, Prada defended itself, saying fur was part of fashion tradition. But after continuous pressure, Prada finally announced in 2019 that it would stop using animal fur. This move was welcomed worldwide and improved Prada’s image.

Image Restoration Theory: Prada’s initial strategy was evasion of responsibility, where they tried to shift the blame by saying fur use was tradition in fashion. However, this strategy was weak, because modern consumers, especially young people, no longer accept such arguments. Later, Prada changed to corrective action, which is the most effective strategy in such cases. By announcing a complete ban on fur, they showed they were serious about making change. This helped restore their brand image and even won them praise from animal rights groups.

Prada Case 5 – Diversity and Inclusion Criticism

Prada was also accused of not showing enough diversity in its advertisements, runway shows, and leadership roles. Most of their models were white, and people from other communities were not well represented. Activists and fashion critics raised this issue on social media, saying Prada was ignoring inclusivity. Prada later admitted their mistake and promised to change. They started diversity councils, mentoring programs, and shared reports to prove they were improving representation.

Image Restoration Theory: Prada first admitted that they had failed in promoting diversity. They then followed with corrective action, such as creating councils and programs to improve inclusivity. They also used reduction of offensiveness, which means trying to highlight the positive steps they were taking so people would see them in a better light. This combination of strategies helped show sincerity.

Prada Case 6 – Environmental Footprint and Sustainability

Prada was criticized for harming the environment through use of plastics, wasteful production, and lack of eco-friendly practices. Young customers especially demanded sustainable fashion. Investigative reports and activists put pressure on the brand. At first, Prada tried to show that they already had some eco-friendly projects, but people felt it was not enough. Later, Prada took bigger steps, such as using recycled materials, setting goals for carbon neutrality, and updating the public on their sustainability journey.

Situational Communication Theory: Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) explains that when a company is seen as fully responsible for a problem, it must take corrective action. Prada faced this with criticism for harming the environment through plastics, wasteful production, and lack of sustainability. At first, it tried to highlight small eco-friendly projects, but this minimization did not convince people. Later, the brand shifted to stronger steps like using recycled materials, setting carbon-neutral goals, and sharing progress updates. These actions showed responsibility and helped reduce criticism, while also improving Prada’s image in a global market where sustainability is highly valued.

Prada’s Crisis Responses under SCCT

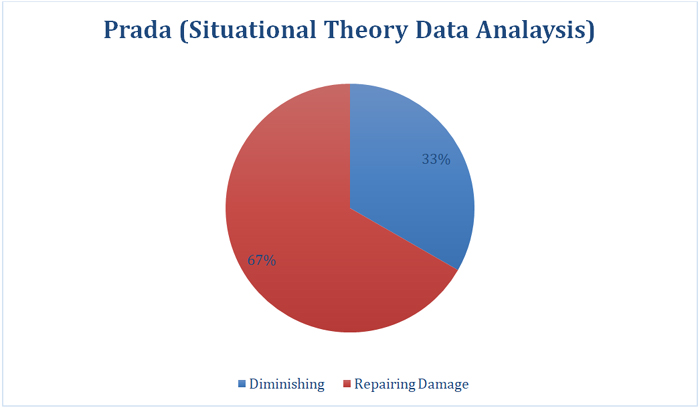

Prada’s responses under SCCT are heavily skewed towards repairing reputational damage (67%), with diminishing used in 33% of cases. Interestingly, there were no instances of denial or accepting fault. This distribution indicates that Prada preferred accommodative strategies when responsibility was high, often trying to rebuild trust by rethinking collections, issuing clarifications, or signalling future collaborations. Unlike Zomato’s mixed approach, Prada displayed more consistency by focusing on repairing and reducing harm. This pattern reflects the global luxury industry’s recognition that brand reputation is fragile, and proactive steps to repair trust are essential when dealing with culturally sensitive controversies.

Prada’s Crisis Responses under Image Restoration Theory

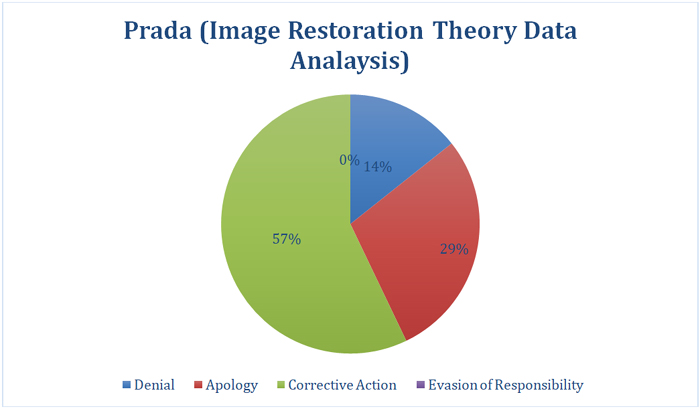

Through the Image Restoration Theory framework, Prada’s responses show a clear preference for corrective action (57%) supported by apology (29%). Denial was minimal (14%), and evasion was entirely absent. This indicates a stronger willingness to accept responsibility and make tangible changes when facing global criticism. Corrective steps, such as removing products, banning fur, or adopting sustainability measures, were central to Prada’s crisis handling. The supporting role of apology further reinforced sincerity, signaling openness to reform. The lack of evasion highlights Prada’s sensitivity to public opinion, reflecting how luxury brands depend on ethical credibility to sustain their premium identity.

Prada Cases Data:

| 1 | Situational | Denial | Accepting Fault | Diminishing | Repairing Reputational Damage |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| 2 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ||

| 3 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | ||

| 4 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | ||

| 5 | Image | Denial | Apology | Corrective Action | Evasion of Responsibility |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ||

| 6 | Situational | Denial | Accepting Fault | Diminishing | Repairing Reputational Damage |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔ |

Conclusion:

This study shows that Digital PR and Online Reputation Management are very important for brands in today’s digital world. They are not only used to handle problems but also to build strong and positive brand stories. The cases of Zomato’s Pure Veg Fleet and Prada’s Kolhapuri sandals give us useful lessons on how these practices work in reality.

The first objective of this study was to see how Digital PR and ORM help in creating positive stories. From the Zomato case, we see that quick communication and clear explanation can help a brand present itself in a positive way even during controversy. Zomato managed to explain its intentions and tried to reduce the negative reaction. On the other hand, Prada failed to create a positive story because it did not give proper credit to the Indian origin of Kolhapuri sandals. This shows how important it is for a brand to respect culture and give value to originality.

The second objective was to check how effective these practices are. The examples show that the success of Digital PR and ORM depends on speed, honesty, and sensitivity. Zomato’s fast response reduced damage, while Prada’s slow and weak response made the issue worse. This proves that the right strategy at the right time can make a big difference.

The third objective was to understand how these practices help in the long term. Good Digital PR and ORM build trust, and trust is the foundation of long-term brand strength. A brand that listens to its audience, respects culture, and responds quickly can survive in competitive markets. Companies that ignore these practices risk losing credibility and customer loyalty.

In the end, both cases prove that Digital PR and ORM are not just short-term tools for solving problems. They are long-term strategies that help brands grow, protect their image, and remain strong in tough situations. Brands that use them wisely can turn challenges into opportunities and build lasting relationships with their customers.

References:

- International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts. (2025). Research paper IJCRT2504936. IJCRT. https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2504936.pdf

- NDTV Profit. (2025, April). Fashion luxury brand Prada Kolhapuri chappal sandal cultural appropriation row. NDTV. https://www.ndtvprofit.com/opinion/fashion-luxury-brand-prada-kolhapuri-chappal-sandal-cultural-appropriation-row

- International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews. (2025). Research paper IJPRR25947. IJRPR. https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V5ISSUE4/IJRPR25947.pdf

- Dean Francis Press. (2024). Article HC001542. Dean Francis Press. https://www.deanfrancispress.com/index.php/hc/article/download/770/HC001542.pdf/3606

- Buddy Infotech. (2024). Case studies in online reputation management (ORM): Real world examples and lessons learned. Buddy Infotech. https://buddyinfotech.in/blog/case-studies-in-online-reputation-management-orm-real-world-examples-and-lessons-learned/

- International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews. (2025). Research paper IJRPR38048. IJRPR. https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V6ISSUE1/IJRPR38048.pdf

- Frontiers in Communication. (2022). Article: 1009359. Frontiers Media. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.1009359/full

- University of Kashmir. (n.d.). Journal article. University of Kashmir. https://deanbs.uok.edu.in/Files/6d8be055-fc07-4110-8b8a-48477e9b960a/Journal/2e36b2ec-d757-4d1e-8607-8daa9351716f.pdf

- Journal of Research in Business and Economics. (n.d.). Article 67. JRBE. https://jrbe.nbea.org/index.php/jrbe/article/download/67/55

- Wildnet Technologies. (n.d.). How Maggi noodles became a household name in India. Wildnet Technologies. https://www.wildnettechnologies.com/case-studies/how-maggi-noodles-became-a-household-name-in-india

- Pepper Content. (2023). 4 Zomato ad controversies: What to learn from them. Pepper Content. https://www.peppercontent.io/blog/4-zomato-ad-controversies-what-to-learn-from-them/

- Social Samosa. (2013, February). Social media and employee evangelism. Social Samosa. https://www.socialsamosa.com/2013/02/social-media-and-employee-evangelism/

- (n.d.). Crisis PR done right in the fashion industry. 5W Public Relations. https://5wpr.net/crisis-pr-done-right-in-the-fashion-industry/

[1] Faculty, Dept. of Advertising & Public Relations, MCNUJC, Bhopal